Some of my earliest memories are of having my foot measured at a shoe store in suburban New Jersey. I’m a little unclear as to why this memory is so vivid, but it might have something to do with those visits also being paired with a soft pretzel. I can still remember my mother scraping comically large salt grains into the trash before I could get a bite of strip-mall, de-salted pretzel. Salt wasn’t something I was allowed to have much of as a kid, so opportunities didn’t come along often. While most of that salty goodness ended up in the Meadowlands, the residual salt was more than enough to keep me happy before my mother needed to duck into Macy’s to discover the latest that early-1990s office-core had to offer.

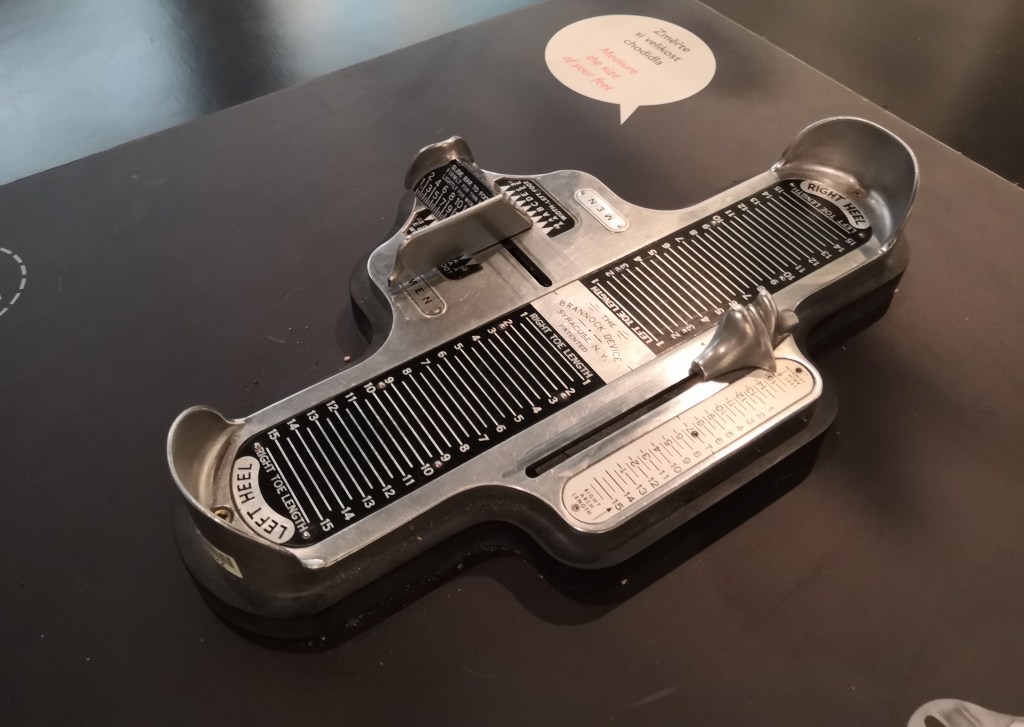

In retrospect, I had probably peaked in terms of the simplicity of the things that made me happy, but it has made me wonder: why did the shoe salesman need to measure our feet? At some point, that store closed and we migrated to Payless down the road, where foot measurement was magically no longer necessary. I honestly can’t remember the last time I’ve seen a Brannock Device, but maybe I’m just not looking hard enough. Allegedly, more than a million of these devices have been sold, and you can still purchase one for $87.25… somebody must be keeping them in business.

Brannock Device from shoe museum in Zlín, Czechia. No word on what the soft pretzel situation is like at this museum. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

I do wonder how much difference the measurement really makes when buying a mass-produced shoe. Just trying the shoe on seems like a pretty foolproof system, but there’s something appealing about the act of quantifying our lives. Knowing how many steps I take in a day, what my pulse rate is, how my lipids change from one doctor’s visit to the next. It has always felt like collecting this information gives me a deeper understanding of who I am. That said, another part of my brain is screaming, “Who gives a shit if it doesn’t change the outcome?” If my unmeasured foot ends up in the same shoe, why introduce the extra step?

Shoe-Fitting Like It’s 1925

Of course, leave it to the 1920s to look at a perfectly good system and ask, “But what if we added radiation?” Enter the Shoe-Fitting Fluoroscope.

Following the discovery of X-rays in 1895 by Wilhelm Röntgen, the technology quickly became a novelty. By 1896, Thomas Edison had developed a practical fluoroscope that used a calcium tungstate screen, which fluoresced when exposed to X-rays. This allowed for real-time images of bones in motion, making it attractive for medical applications.

Depending on who you ask, you might get a different answer about who invented the shoe-fitting fluoroscope. The most credible claim seems to lie with physician Jacobe Lowe, who filed a patent in 1919. Lowe branded his invention the Foot-O-Scope, and for the price of $900 (roughly $14,000 in today’s dollars), a shoe store could offer customers live-action shots of their foot bones inside their shoes.

And of course, no cash grab of this variety would be complete without some compelling ad copy. Here’s an excerpt from a radio commercial for the Adrian Special shoe-fitting machine:

Every parent will want to hear this important news! Now, at last, you can be certain that your children’s foot health is not being jeopardized by improperly fitting shoes. [STORE NAME] is now featuring the new ADRIAN Special Fluoroscopic Shoe Fitting machine that gives you visual proof in a second that your children’s shoes fit.

Radio Commercial for the ADRIAN Special Fluoroscopic Shoe Fitting machine

Such marketing resulted in widespread adoption throughout the 1940s and 1950s. This might seem paradoxical, given that during the same period the risks of radiation exposure were becoming more widely recognized. The issue was non-trivial: these machines produced relatively high levels of radiation. While this posed less of a problem for customers, shoe salesmen lacked protective gear and were often exposed repeatedly—some performing as many as 400 fittings a day.

By 1949, Charles Williams had published measurements of radiation output from 12 operating machines in the New England Journal of Medicine, and L.H. Hempelmann followed with another article in the same journal detailing the potential dangers. Williams’s work showed that some machines exposed a child’s feet to 19 times the radiation per second that was considered safe for X-ray workers at the time. By the 1950s, professional medical associations began advising against the use of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes, and by 1960, 33 states plus Washington, D.C., had banned the practice or adopted strict regulations. Still, there are reports of such instruments being used in the U.S. as late as 1981 (looking at you, West Virginia).

Does Any of This Matter?

Remove the obvious health concerns, and I still have questions: why would a picture of the bones in the foot have anything to do with the quality of the fit? I understand that bones scrunched together might look odd, but I’m not convinced it’s a true indicator of anything. Since so much of the foot is soft tissue, I’m perplexed as to why the fluoroscope was considered superior to our own subjective perceptions of comfort. My own attempt at a literature search has left me wanting. Systematic reviews give the impression that the available evidence is very limited when it comes to what actually makes a shoe comfortable. I imagine cultural preferences also play a role, as detailed by The Shoe Snob.

At the end of the day, comfort is subjective, and I think most of us should probably trust what feels good over some arbitrary metric. That’s why I still put my faith in a good soft pretzel over the quantified self. One, at least, comes with a healthy dose of nostalgia.

Want to learn more about X-rays? Be sure to read Try to stay still for your bone portrait.

Discover more from The Retro Scientist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This hit in all the right places – soft pretzels, childhood nostalgia, and that constant pull between data and intuition. You’ve got a real gift for making nerdy feel… oddly charming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much! That’s really nice of you to say! If I ever write a book I want “gift for making nerdy feel… oddly charming” to be on the dust jacket.

LikeLike