In 1903, French physicist Prosper-René Blondlot announced something extraordinary: a brand-new form of radiation he called “N-rays” after his home base at Nancy University. According to Blondlot, these mystery rays could make a barely visible spark a little bit brighter.

Soon, French labs were identifying N-rays everywhere. Possible sources of N-rays included:

- A specialized gas burner called a WeIsbach mantle

- An incandescent lamp called a Nernst glower

- Heated silver and sheet iron

- The sun

- Living and dead bodies

- Nerves

- Muscles

- Isolated enzymes

This list of sources remains so broad and varied one starts to wonder what couldn’t produce N-rays. The only limitation seemed to be imagination. By 1906, nearly 300 articles had been published on the topic. There was one small issue standing between Blondlot and immortality in Halliday and Resnick’s Fundamentals of Physics: N-rays don’t actually exist.

Blondlot’s Spark of Discovery

In some ways Blondlot was a victim of his era. He was physicist at a time when new types of radiation were being discovered regularly. Röntgen had just discovered his mysterious X-rays in 1895. The next year Henri Becquerel discovered that Uranium produced radiation, based on black spots produced on photographic plates. Additional work on radioactivity was conducted by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898. Ernest Rutherford focused on alpha and beta radiation in 1899. Paul Villard discovered gamma rays in 1900. This primed physicists everywhere to be on the look out for new mystery rays.

It was during this period right after 1895, that Blondlot became deeply interested in X-rays. While working with polarized X-rays, Blondlot believed he had found a new type of radiation he was calling N-rays, that could be bent by a quartz prism and was capable of making a faint spark slightly brighter.

Diagram illustrating Blondlot’s experimental setup used to detect ‘N-rays’ with spark measurements and photographic plates.

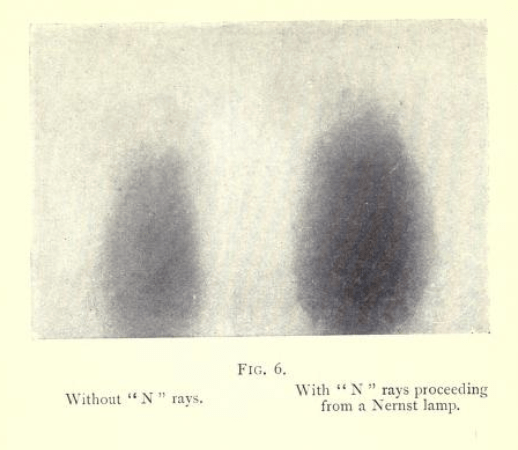

He wanted to confirm his results. To do this, he developed the apparatus above. It assesses changes in spark intensities using photographic plates. Water was believed to be opaque to N-rays, thus producing an N-ray free environment. Repeated sparks always produce a black spot on a photographic plate. The presence of N-rays was believed to cause a brighter spark resulting in slightly darker spot, as seen in the figure below.

Blondlot’s photographic “evidence” of N-Rays as published in “N” rays: a Collection of Papers Communicated to the Academy of Sciences

There were a string of successful French “replication” studies, which found the long list of N-ray sources detailed previously. A battle ensued, which should surprise no one. It was time to fight over who deserves credit for discovering this imaginary radiation first! For example, Gustave Le Bon claimed to have discovered a similar mystery radiation 7 years earlier. This claim is truly fantastic given that, once again, N-rays are not a real thing.

Wood in Nature Strikes Back

As one might imagine, not every physicist could replicate Blondlot’s results. Particularly on the pages of Nature it was not hard to find contemporaries throwing shade:

“Personally, I have repeated most of M. Blondlot’s experiments, but I have not been able to discern the slightest trace of any of the remarkable phenomena he describes.”

A.A. Campbell Swinton in Nature (January 1904)

At the start of 1904, the future of N-rays seemed bright. Enter American physicist Robert W. Wood, who manged to practically single-handedly upend the field. Wood was uniquely suited to this task:

- As an internationally renowned expert in spectroscopy, he specialized in the analysis of electromagnetic radiation

- Wood had already “wast[ed] a whole morning” trying to replicate Blondlot’s work. As a result he was eager to see “the apparently peculiar conditions necessary for the manifestation of this most elusive form of radiation”

- He was a well known prankster who enjoyed using his skills of deception to debunk pseudoscience

With these skills in tow, Wood traveled to the University of Nancy to witness Blondlot’s N-ray experiments first hand. He describes his 3 hour experience in a September 29, 1904 letter to Nature. It soon became clear to Wood what the limitations were of Blondlot’s experimental apparatus. The spark intensity seemed to vary widely introducing a pretty substantial source of experimental error. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly Wood notes the limitations of the apparatus and results shown earlier:

“The two images (with n-rays and without) are built of ‘instalment exposures’ of five seconds each, the plate holder being shifted back and forth by hand every five seconds. It appears to me that it is quite possible that the difference in the brilliancy of the images is due to a cumulative favouring of the exposure of one of the images, which may· be quite unconscious, but may be governed by the previous knowledge of the disposition of the apparatus.”

J. W. Wood in Nature (September 1904)

This potential to introduce subconscious cumulative error, was the Achilles heal of these experiments. It is perhaps no coincidence that many of Blondlot’s most ardent supports remained loyal even after this Nature article. These colleagues were geographically close to Blondlot. They would have been most influenced by his prior reputation.

The final nail in the N-ray coffin was a simple aluminum prism. Blondlot had suggested that N-rays could be bent by an aluminum prism. He claimed this could happen using a beam of N-rays focused by an aluminum lense. It was argued that this should produce a full “N-ray spectrum.” This would be similar to what is seen when visible light is passed through a glass prisms. Ever the prankster, Wood decided to see what would happen if he removed components of the experimental setup. He wanted to check the effect on the results when the experimenters were not aware of the modifications. Wood writes:

“I subsequently found that the removal of the prism (we were in a dark room) ‘did not seem to interfere in any way with the location of the maxima and minima in the deviated ( !) ray bundle.“

J. W. Wood in Nature (September 1904)

In other words, absence of the prism had no impact on the results. In most labs today, sabotaging an experiment as a visitor would be frowned upon. However, I think in this case we can probably forgive Wood for his transgression. To his credit he does propose an experiment to help definitively evaluate the existence of N-rays. His proposal was to blind the operator to which side was being exposed. Without that information subconscious bias would be limited.

Blondlot was never willing to do the experiments necessary to definitively test for the presence of N-rays. To the credit of French physicists, many repeated their prior experiments with controls. They wanted to address Wood’s criticism. When that was done, the N-rays vanished. In response to this growing replication crisis, the French Journal Revue scientifique ultimately proposed that Blondlot use two sealed boxes to conduct his experiments. One contained an alleged N-ray emitter (tempered steel). The other was a weight matched piece of lead, which was not supposed to emit N-rays. Using Blondlot’s method of choice he would have to identify which box was which. Blondlot thought for a while but ultimately replied:

“Permit me to decline totally your proposition to cooperate in this simplistic experiment; the phenomena

Prosper-René Blondlot

are much too delicate for that. Let each one form his personal opinion about N-rays, either from his own experiments or from those of others in whom he has confidence.”

The Hardest Part of Science Lies Within Ourselves

Blondlot went to his grave believing in N-rays. No amount of evidence was ever sufficient to change his mind. Much like “Flat Earthers” who reverse fit evidence to fit their preconceived notion of the way the earth operates. For this reason good science is hard. It challenges our preconceived ideas. It pushes to question what we know. It asks us to consider new evidence that may damage our pride. It occasionally forces some of us to take someone else’s prisms to make a point. However, this situation rarely arises for most of us.

Blondlot’s folly is a reminder to us all. Even the Spock-like among us, who consider ourselves to be doing objective “hard” science, are still subject to unconscious bias. It is better to be aware of those biases and control for them, rather than pretend we don’t have them. Otherwise we’re all destined to spend our time chasing our wishful thinking.

For a great read on rays that did pan out, be sure to check out Try to stay still for your bone portrait. Find out why Loise Lane may want to start measuring her radiation exposure.

Discover more from The Retro Scientist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Et tu Brute? Stories of betrayal and why you shouldn’t lose sleep over them. | The Retro Scientist